This article, originally posted in Japanese on 20:00 May 03, 2025, may contain some machine-translated parts.

David Rosenthal, a digital archivist who has been working on the long-term preservation project at Stanford University Libraries since 1998, has summarized the contents of his lecture '

Archival Storage ' that he gave at the University of Berkeley in March 2025 on his blog. In this lecture, Rosenthal argues that 'it is a misconception that archive data must be stored on semi-permanent media.'

DSHR's Blog: Archival Storage

https://blog.dshr.org/2025/03/archival-storage.html

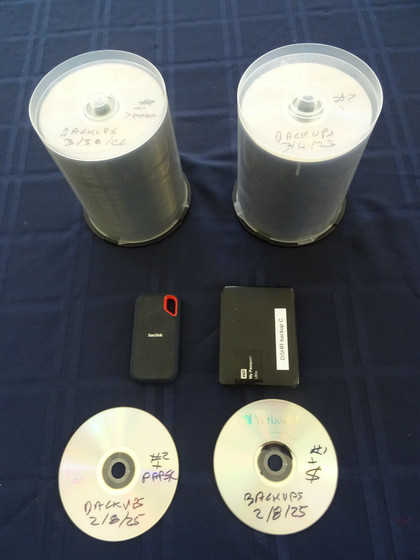

Typically, Rosenthal backs up his email and web servers once a week to a Raspberry Pi on the same network, then does incremental backups every day, and writes these backups to two DVD-Rs each week. He rotates between three external hard drives to create a full backup of his desktop PC every night, and backs up his iPhone every day to a MacBook Air. He also rotates between three external SSDs to perform a Time Machine backup of the MacBook Air every day, and moves the DVD-Rs and used SSDs and HDDs to a different location every week.

The purpose of these backups is to ensure that in the event of a disaster, such as a fire or ransomware, you can recover as close as possible to the state you were in before the disaster, and in the worst case scenario, you won't go back more than a week.

The important point here is that 'the useful life of backup data is only the time between the last backup before the disaster and recovery.' Rosenthal says he keeps hundreds of DVD-Rs, but the only time the DVD-Rs are accessed a few weeks after writing is during an annual ' optical media durability check .' Rosenthal reports that this check confirms that data can be read normally from CD-Rs that are more than 20 years old and DVD-Rs that are nearly 18 years old without any special storage measures.

However, Rosenthal's reason for backing up with DVD-R is not because he found that DVD-R media can last for more than 15 years, but because he values the write-only nature of DVD-R. The advantage of being write-only is that the backup data can be destroyed but not changed.

Rosenthal argues that backups and archives are fundamentally different. Backups are merely insurance for short-term storage, and the longevity of the media is essentially irrelevant, but the fundamental design goal of archive storage systems is to 'reduce the cost of long-term storage by tolerating increased access latency,' he emphasized.

For example, the private organization Long Now Foundation is building a clock called the 'Clock of the Long Now' that will keep time for more than 10,000 years, and is also considering creating an archive that will be preserved for 10,000 years.

However, while Rosenthal acknowledges that he is looking at a very long-term preservation of 10,000 years, he points out that 'a time scale of 10,000 years is at least two orders of magnitude longer than the time frames currently considered in digital preservation discussions.' Given that the first computers capable of storing programs first appeared only about 75 years ago, and the overall history of digital technology is very short, 'ultra-long-term preservation of 10,000 years may be ideal, but there are challenges such as rapid changes in technology, compatibility issues, and media degradation, and even aiming for a preservation period of 100 years is quite ambitious,' Rosenthal points out.

Similarly, research is underway to use DNA as a long-term data storage medium, but in a 2019 experiment it took 21 hours to write and read five bytes of data, and the operation cost $10,000 (approximately 1.4 million yen), so it cannot be considered a practical archival medium. Rosenthal warns that the economics of the entire system are more important than the physical lifespan of the media, and that excessive expectations for 'semi-permanent media' will overlook the essential challenges of digital preservation.

In particular, Rosenthal points out five commonly held misconceptions about archival storage:

1: Misunderstanding the market size

New technologies developed in laboratories, including DNA storage, are expected to be able to store large amounts of data for long periods of time in the future, but in reality, the market for storage dedicated to archiving is only a small portion of the total storage market. (PDF file) According to IBM data , even LTO tape accounts for less than 1% of the total media market in terms of value and less than 5% of the total capacity, making the market for storage dedicated to archiving very small. Rosenthal argued that the discontinuation of Sony's Optical Disc Archive in 2023 due to market insufficiency also shows how small the market is.

2. Misunderstanding timescales

It is often thought that new storage technologies will appear on the market soon, but in reality, it takes a very long time for storage technologies to be developed and brought to market. For example, Seagate's next-generation hard disk technology ' HAMR ' has been in research for 26 years, and it took 2025 for it to actually be shipped to the market. Silica data technology , which stores data on glass, has been researched for 15 years, and DNA storage has been researched for 36 years, but both are expected to take more than five years to be brought to market.

3. The misconception that it will become a consumer product

While there is sometimes hope that new archiving technologies will become consumer products, the reality is that the overall cost of the archive system is much higher than the media itself, and archival storage needs to operate at a data center scale to be economical. It is economically impractical for individual consumers to adopt these technologies, and cost-effective archiving solutions will never be within the reach of consumers, Rosenthal said.

4. Misunderstanding consumer interest

Consumers don't care about what media their data is stored on, only the big cloud companies do. Users trust that their data is safe in the cloud, but they don't really see the need for backups or archiving. Even if you use a service like Amazon Web Services' Amazon S3 Glacier storage class , you don't know what media your data is stored on.

5. The misconception that natural data degradation is the only problem

While the natural degradation of data tends to be the focus, even semi-permanent media requires multiple copies to keep data safe, says Rosenthal. No media is perfect, and there is a concept called Unrecoverable Bit Error Rate (UBER). For example, a typical disk has an UBER of 10-15 , which means that up to eight errors can occur when reading one petabyte. In addition, it is important to note that even semi-permanent media such as silica and DNA are vulnerable to other threats such as fire, flood, earthquake, ransomware, and internal attacks. Therefore, multiple copies must be maintained even for long-term storage, which significantly increases costs.

Rosenthal urges us to return to the core tenet of LOCKSS (Lots Of Copies Keep Stuff Safe) : that given limited budgets and a range of realistic threats, data is more likely to survive as many cheap, unreliable, loosely coupled replicas than as a single, expensive, durable copy.

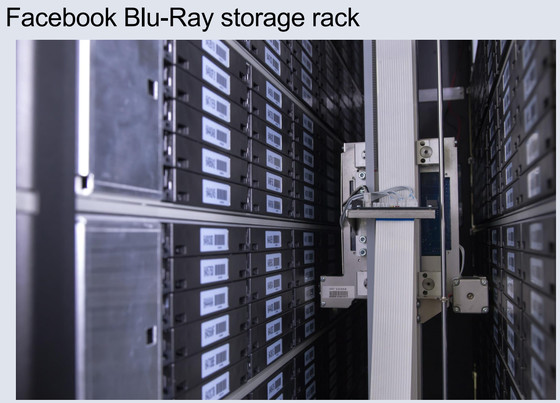

For example, Facebook's data storage , announced in January 2014 (PDF file) , will accommodate approximately 10,000 100GB Blu-Ray discs, boasting a capacity of 1 petabyte per rack. A writable Blue-Ray disc costs around 100 yen per disc, so the media cost per rack is about 10,000 yen. Considering that data storage using 20 IBM LTO tapes costs at least $20,000 (about 2.8 million yen), and the price of two LTO tapes is about $4,000 (about 650,000 yen), Facebook's archive data system can be said to be very inexpensive. Rosenthal also appreciated that Facebook operates this system on a data center scale, while utilizing warehouse space that is more cost-effective than a regular data center, and optimizing costs such as power, cooling, and staff. This Facebook archive data system is an example of Rosenthal's argument that 'archiving is an economic problem, not a technical problem.'

He quoted Brian Wilson, chief technology officer at cloud storage company BackBlaze, as saying , 'Doubling reliability is only worth 0.1% of the increased cost.' He added, 'The lesson from Wilson's point is to design for failure and buy the cheapest parts possible.'